After three years and 72 flights through the thin martian atmosphere, the tiny helicopter “Ingenuity” has had its historic mission brought to an end by a damaged rotor blade. I know it’s just a little four-pound robot that has been bopping around on an uninhabited planet 140-million miles from Earth, but its demise made me sad. This is personal.

You see, I worked for NASA for part of my career, as a Senior Special Projects Producer for NASA-TV. Space exploration is a topic near and dear to my heart. I rubbed elbows with John C. Mather, a Nobel Laureate and astrophysicist who can actually explain to a layman like me how the universe has formed since the Big Bang. I did lengthy interviews with many of the men who walked on the moon including Neil Armstrong, and Buzz Aldrin, the first men to set foot on the lunar surface, and Eugene Cernan, who was the last. I also interviewed the men from Mission Control who got them there and back in one piece. These men were my childhood heroes and that adoration has stayed with me for life.

In documentaries I produced for NASA about the Journeys of Apollo, and the many other missions devoted to mind-bending exploration of the universe, I recorded in their own words and voices, the conviction and dedication they brought to their work. These people, just as human as you and I, endured brutal physical challenges. They offered their lives for the loftiest of goals, and some paid that price. They accomplished phenomenal tasks in a time when computers were just being invented, doing the math with pen and paper, figuring out how to rendezvous three bodies in motion (the earth, the moon, and the capsule) with pinpoint precision.

Imagine what it must feel like to set foot on another celestial body, and look up to see planet earth shining in the sky above your head. You’ll have to imagine it, because you will never actually do it. They did.

That spirit is shared by every man and woman who works for the space agency, in a sprawling network of facilities spread throughout the country in a politically correct fashion, so as to provide not only revenue to every congressional district, but also to spread the honor and glory of working for a government entity whose goal is purely to advance our knowledge of the universe around us.

“Failure is not an option,” is a phrase made famous by Gene Kranz, the NASA flight director who was charged with getting the stranded astronauts of Apollo 13 safely back to Earth. In reality, failure in space travel may not be what we chose, but it is always present. The NASA Historical Log of missions to Mars currently catalogs 48 missions aimed at our closest neighboring planet, and half of them (heavily weighted towards the earliest years of exploration) have failed. But about two dozen Martian attempts have been successful. Not all are on the surface. Some, like the Mars Reconnaisance Orbiter (Now in its 18th year!), circle the red planet from above, gathering photos and data.

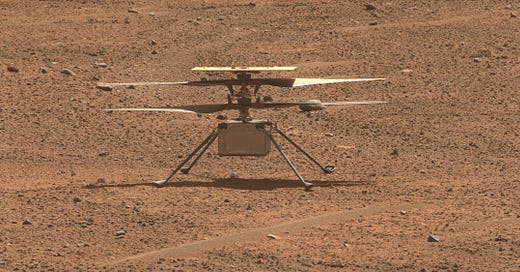

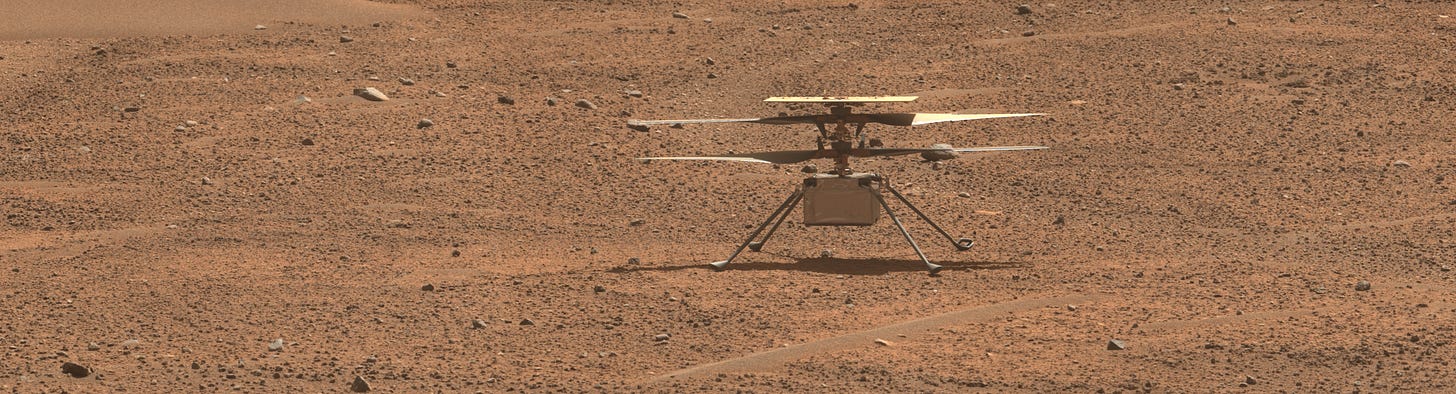

In places beyond the moon, we humans must rely on robotic explorers, for now. A large portion of such missions are operated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory near Pasadena, California. JPL was responsible for the Ingenuity project. The little four-pound helicopter hitched a ride to mars in the belly of the car-sized Perserverence Rover, which touched down on the surface of Mars in February of 2021. Ingenuity was supposed to be little more than a proof of performance test project. With an atmosphere only about one-percent as dense as Earth’s, no one really knew for sure that the tiny bird could even fly there.

But fly it did, in spectacular fashion. NASA originally planned just five flights over a 30 day period. Success of that magnitude would have been an historic victory for the agency. Instead, that turned out to be just a warm-up. The statistics of this mission are phenomenal. Over three years and a whopping total of 72 flights, Ingenuity shattered even the wildest dreams of the most optimistic engineers at JPL. In total, the amazing flying machine logged 128.8 minutes of flight time, covering a total distance of 17 kilometers (10.5 miles), at altitudes up to 24 meters (78.7 feet) above the martian landscape. Operating between 2400 and 2900 revolutions per minute, its four-foot long carbon fiber rotors made somewhere around 350,000 revolutions. Its tiny batteries even survived insanely cold Martian winters, much to the amazement of all.

Ingenuity gave us bird’s eye views of a planet where no birds fly. It helped us search for places where water once flowed over what is now dusty and, probably, lifeless terrain. If there ever was life there, Ingenuity may have already helped us find the clues we need to learn about it. NASA has an interactive website dedicated to this mission that deserves your attention.

Ingenuity didn’t just wander aimlessly around, either. The team at JPL flew Ingenuity in partnership with the Perserverance rover, providing scouting reports for its scientific tool-packed partner. The little bugger flew so far and for so long that NASA had to rewrite its mission plan over and over again.

“The historic journey of Ingenuity, the first aircraft on another planet, has come to an end,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson announced yesterday. Something went wrong during Ingenuity’s 72nd flight on January 18 and the helicopter executed an autonomous emergency landing. Since Mars is much too far away to fly the helicopter in real time from here, engineers would upload instructions to Ingenuity, and the actual control of a flight was up to the helicopter and its miniscule onboard computer. We don’t yet know what went wrong, but that computer deemed the emergency landing to be necessary.

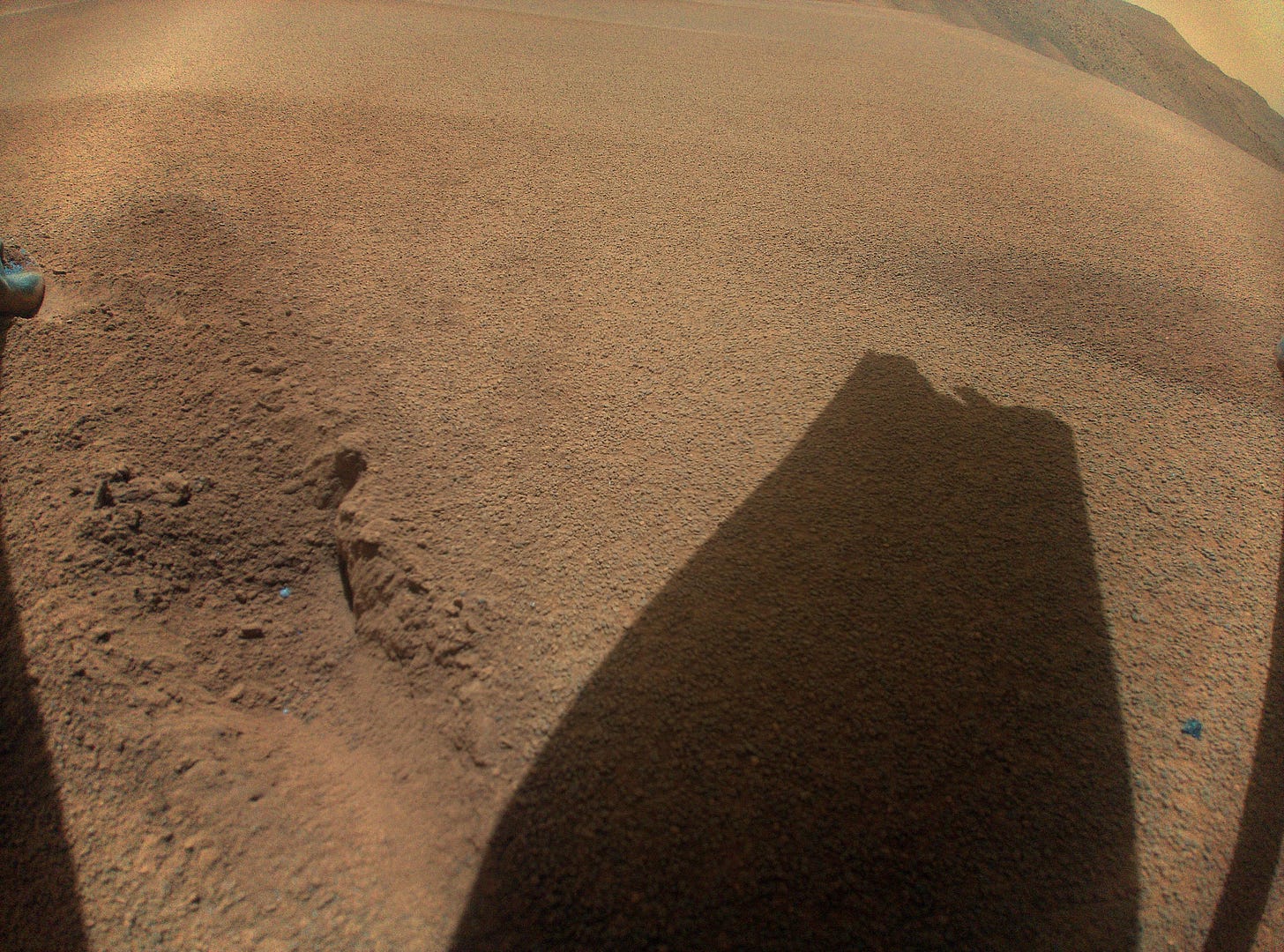

The Perserverance rover is too far away from Ingenuity at the moment for JPL to use its cameras to inspect the damage to the helicopter. But Ingenuity has sent back this picture of the shadow being cast on the martian soil by what appears to be a broken rotor:

The jagged end of that shadow should look more like the smoothly curved tip of an airplane wing. Engineers think the rotor may have struck the ground, causing the damage and forcing the emergency maneuver. There may be more damage than that, but even this is enough to permanently ground the plucky little robot for all eternity.

It is, as I said, a sad moment for a space junkie like myself. But, as a former NASA employee, it is also a proud moment. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration, despite all of its faults, is one element of federal government that should make every American of every political persuasion proud.

We haven’t set a human foot on the moon in more than 51 years. With completion of the Ingenuity helicopter mission on Mars, another chapter of exploration also comes to a close. But don’t put the book away just yet. NASA isn’t done expanding our knowledge of the universe around us.

Humans will go back to the moon (although I have serious doubts about the current plan to do so), and someday our humble but determined species will walk on the surface of Mars. What a fitting ending it would be to Ingenuity’s mission if, one day, a human being in a complicated spacesuit flying an even more sophisticated rotary aircraft through the Jezero Crater on Mars, lands alongside the long-silent little aircraft that was the first to fly there, and brings it back to take its rigfhtful place of honor in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, in Washington, D.C.

That might sound like an impossible dream for now, but in the words of NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, “That remarkable helicopter flew higher and farther than we ever imagined and helped NASA do what we do best – make the impossible, possible.”