I have just witnessed the third paradigm shift of my life. I grew up, first with a crayon in my hand, then a pencil, then pen, and when I was old enough I transitioned to a manual typewriter. All of those instruments used to record information existed before me, so the move from one to the next was more a matter of growing into it, rather than any kind of sea change of technology. Okay, the electric typewriter I received as a gift was certainly a significant transition, but it’s main benefit was an increase in speed at which I could record my thoughts on paper. However, I was still hitting one key at a time, just as I am doing right now.

The first paradigm shift for me came in 1983. I was the Assignment Editor in the newsroom of a television station in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Keeping a paper record of every story we did, tracking the work shifts, assignment of each reporter and camera person, tracking the schedules of those assignments, maintaining an ever-evolving schedule of upcoming stories, and dozens of other data sets was mind-boggling.

Computers, in their crudest forms, had been around since the 1950’s, but they were paper card-based monstrosities called mainframes that cost fortunes, were only accessible to the largest of companies and governments, and were quite limited in their abilities. They could help sort data into usable piles, and that’s about it.

When an upstart company that called itself Apple released a desktop computer in January of 1983, everything changed. The accounting department at that little television station bought a LISA, as Apple’s computer was known, and began using it to track all of the sales and financial data for the station. Realizing that the feisty little machine, with its dual floppy disc drives (each capable of holding a mere 871 kB), flickering green screen, and dot-matrix printer could also help me out, the accounting manager gave me access to it for my data tasks.

LISA (an acronym for Local Integrated Software Architecture) blew my mind. I was able to not only record all the information I had been keeping in notebooks and typewritten forms, but I could sort that information into useful piles just like the big guys. It was a life-changing moment.

Computer development happened quickly in that era and it was only a matter of a few years before I would experience yet another shift of the paradigm I had recently entered. I was sorting my data on the LISA, but as a television journalist, I was still editing my stories for the Six O'clock news one of two ways. We had a mix of film cameras and the first generation of portable video cameras to work with. Videotape had been around for a very long time by this point, so the introduction of the portable video cameras was great, but it felt more like an evolutionary step. So physically cutting pieces of 16MM film into scenes and gluing them together to create a coherent story, or using two videotape machines to essentially do the same thing, wasn’t much of a transition.

The second shaking of my planet happened when computer technology got wedded with those videotape machines, and I could use a computer to actually control those edits. To learn how it worked, I conducted an experiment. I used a video camera to record thirty minutes of the sun setting over an icy winter landscape. At thirty frames per second, that meant there were 54,000 frames of video. The next day, I loaded that tape into the machine, and told the computer controlling it to edit together just one frame from every second. It sounds quaint by today’s standards, but it took the computerized system all night to do the job. The resulting 15 second (450 frame) video of the sun setting at high speed was a shocker to us all. That the computer was capable of doing something in one night that would have literally been an impossible task for an editor to accomplish without going insane, was unbelievable.

The decades since that time have seen computerized video editing grow exponentially, to the point where now almost every new computer shipped contains some sort of video editing program. My colleagues and I are the ones who helped make those programs what they are. I spent most of my career sitting on the cutting edge of this technology, honing it even sharper with my skills and input to the companies who developed the software. At ABC News I had the privilege to work with a good many highly skilled editors and our competitive nature always had us trying to outdo each other with new techniques. Of course, when one of us cleared another hurdle, we would always take pleasure in bringing each other up to speed on how we did it. We were all on the same team, after all.

The third paradigm shift of my life came just last month, and I am still reeling from the shock. It’s name is nearly an oxymoron, but Artificial Intelligence has entered my life.

Yes, I have heard and read about AI for years now but it was, for the longest time, the stuff of science fiction. You have to go all the way back to 1927 to find the earliest roots of artificial intelligence in the movies. A German film called Metropolis used a human-looking robot to prevent the working class from rebellion against the rich. Others followed, of course, including The Day The Earth Stood Still in 1951, and perhaps most famously, HAL9000 in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001:A Space Odyssey in 1968. That movie, arguably, opened to door for dozens of movies and television shows that showed the promises and pitfalls of artificial intelligence, usually in relation to some sort of space travel setting.

But, I digress. For me, AI came home to roost when I went looking for a royalty free image to pair with one of my Distant Perspective commentaries. Since I don’t charge you, loyal reader, for the opportunity to ingest my viewpoints from this far-away haven I now call home, I can’t pay for artwork to accompany my thoughts. When I typed in a Google search begging for a free image, my browser responded with a link to a do-it-yourself, artificial intelligence website where I could create my own graphic images - FOR FREE!

Free being my favorite four-letter-word (Yes, it has competition, but Free stills wins every time), I figured it was time to give AI a shot. I logged onto the site, simply typed in a plain-English sentence describing what I wanted, and within seconds the site sent back a freshly-minted image more stylized and amazing than I could ever have thought of by myself. By typing in one or two more sentences describing changes I wanted it to make to the image, the AI behind the site took no more than a few seconds to regenerate a modified graphic for me that was richer in design, color, and creative individuality than any man-made graphic I have ever seen. The cost to me? Not one penny!

The immediate implication of this stunning advancement in computer-assisted life is still making my head spin. The image I created for free in a few seconds would have taken a human graphic artist days or weeks and many modifications to achieve. I would have had to pay that artist hundreds, even thousands of dollars for the work. The result would also have represented a compromise between what I see in my head, and what the artist sees in theirs. In creative endeavors involving two or more people, compromise is always a part of the equation.

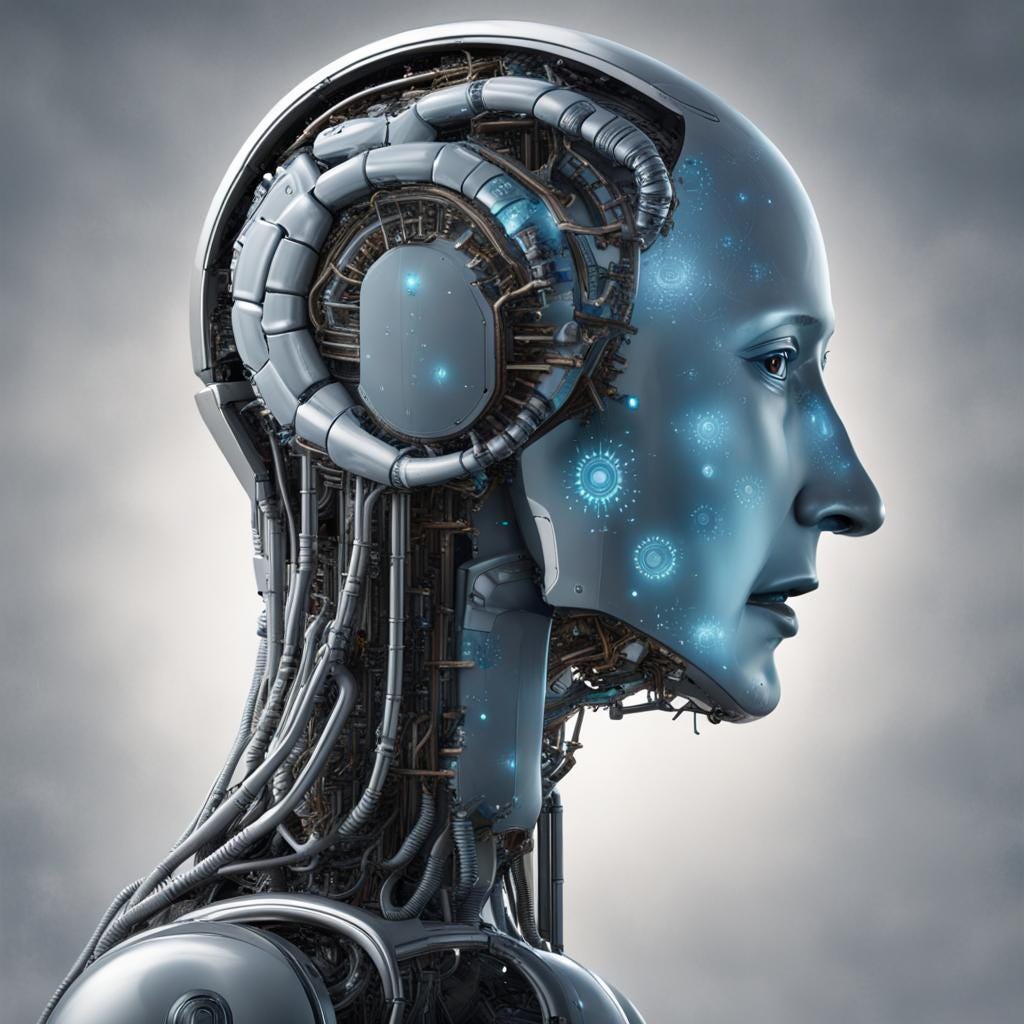

It was so earth-shaking that I just had to do it again. The image of the computerized human head that accompanies this commentary was my second work on the AI site. The words I typed in the instruction box was “A humanized computer with tentacles”. I could have told it to put an Earth in the background, or a starscape, or any of a zillion other thoughts, and the site would have complied. But I wanted to keep it simple to illustrate how little human input it really takes to end up with a fantastic result.

The flipside of this sea change in my ability to work quickly and without cost means that the graphic artists I have worked with in the past just lost my gigs. AI websites like the one I used are literally going to put many graphic artists on the unemployment line. They have just been replaced by a faceless, non-human website being driven by a computer, or some web of machines that are crunching zeroes and ones through a series of algorithms to meet my needs.

That’s just the beginning. My entire commentary could be written by AI. (It isn’t, I assure you.) That means writers, poets, journalists, corporate executives, air traffic controllers, doctors - virtually anyone in an occupation or profession that involves thinking - could soon be replaced by artificial intelligence. Sooner than you think.

Yes, those professionals will learn to incorporate AI into their work flow. My graphic artist can harness this tool to become more productive, and more creative at the same time. That’s true, as far as the argument goes. Even in that case, that artist is going to be able to create far more images than before, meaning that the number of jobs available for graphic artists will be eroded by this advancement. And the fact remains that someone like myself won’t need them at all.

But artificial intelligence doesn’t have a heart and a soul, or so the argument goes. It can never replace the masters of human creativity. It can’t give us the humanity of the Rembrandts, Monets, Picassos, and Dalis of the world. Maybe not, but it can already emulate their styles so well that the average person won’t know the difference. And who’s to say that the AI of tomorrow won’t be able to develop algorithms that find enough “soul” to create a masterpiece.

In fact, AI is training itself to do just that, right now. Even Substack, the host site for this commentary, is using the words authors like me write (I have opted out of this) to train its own AI program to write the way we do. In the Settings for Substack, there is an option line that says, “This setting indicates to AI tools like ChatGPT and Google Bard that their models should not be trained on your published content. This will only apply to AI tools which respect this setting, and blocking training may limit your publication's discoverability in tools and search engines that return AI-generated results.” In other words, if I don’t let Substack’s AI use my words to train its soul, I will be penalized by having the exposure of my commentary limited. It is literally trying to bribe me to give up my human essence in order to learn how to replace me.

There’s more. Even opting out doesn’t mean AI isn’t stealing my thoughts. The line in the setting that says “This will only apply to AI tools which respect this setting” means that AI doesn’t even have to obey my wishes. Effectively, my thoughts and style can be taken from me without my permission, and there isn’t a thing I can do about it.

This incredible technology is just emerging. Extrapolate where it is right now to where it will be in just ten years, and then a hundred. Even then, if a computer can create the world’s next Mona Lisa, that means it can create a million exact copies. Will this art have any value? Will any art? Will any written word? What is even real anymore?

This isn’t some esoteric question for discussion about whether the future will be the embodiment of some utopian ideology, or collapse into the end of humankind. The experiment is already happening. I have seen advertising for a company that sends a client a series of questionnaires about their life. By plugging the answers into an artificial intelligence writing program, it takes only seconds for the system to write a personalized memoir for that person. I have been writing my own memoir for about two years now and I’m not close to being finished. Certainly my story will have more heart and soul in it than the AI version could. But the book would already be for sale, had I gone that route.

This conflict shows up from time to time in those movies that carried prescient warnings about the dangers of handing decision-making over to non-human entities. Yet, even though we’ve seen this coming for nearly a century, the time of reckoning is here and we don’t have the answers.

MIT’s Technology Review outlines six ways AI can be regulated and controlled. Most of the discussion in the article describes treaties and other agreements covering ethics and uses of AI. The London School of Economics and Political Science frets about whether the changes AI will introduce will be controllable. Charles Jennings, whose own experience includes deep involvement with AI that has caused him to write a book about the subject, believes artificial intelligence should be nationalized, becoming the property of the government. Jennings admits in his Politico essay, “Not even the engineers who build this stuff know exactly how it works.”

I don’t know about you but, frankly, I don’t trust the federal government to exercise intelligent, common sense control of a world-changing technology whose inventors don’t know where to look for the brake pedal. I also don’t trust the private enterprises who help build, and now own, AI. I certainly don’t trust foreign governments, treaty agreements, the United Nations, or any of the other solutions that I’ve been reading about. It is, in this very moment, a frightening question without an answer.

Will mankind be able to figure out how to control an intelligence far more powerful than all of us added together; an intelligence that encompasses every known fact; an intelligence that can’t be bothered with emotion; an intelligence that doesn’t care if the graphic artist I used to hire ever works again?

I trust that we will find the answer. I just hope we do it in time.